Abstract

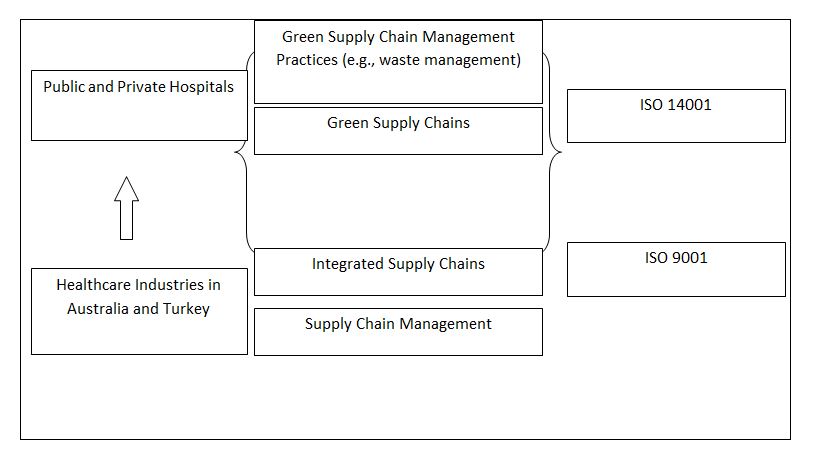

In recent decades, the public’s degree of environmental consciousness has improved dramatically and especially in the light of several industries, including the healthcare business. The healthcare system is among the ones that contribute significantly to the pollution, use of unrecyclable materials, high volumes of waste, and consumption of unrenewable energy. The development of health care has resulted in expanded hospital operations and heightened awareness of hospital sustainability, among other environmental problems. These developments, among other things, have resulted in a worldwide effort that has targeted the formation of global standards to address concerns in many nations that are linked to global environmental management challenges. The goal of this study is to assess the link between green supply management (SCM) implementation, ISO 9001-2015, and ISO 14001-2015 compliance, using the case study from two hospitals. Green supply chain management is still a relatively new concept in hospitals, despite its widespread application in other industries.

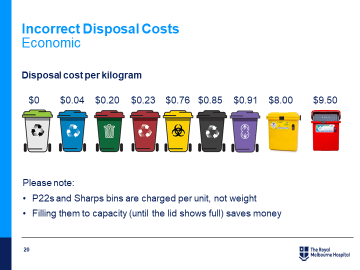

According to the findings of this study, green SCM is a realistic option for hospitals in terms of lowering waste output and associated expenses. There are other benefits for private hospitals, such as enhanced reputation and patient confidence. Furthermore, it indicates that compliance with ISO 9001-2015 and ISO 14001-2015 may effectively enable a hospital to pursue environmentally-friendly practices. Having said that, implementing green SCM is linked with higher short-term expenses while the facility adapts to the new requirements. Furthermore, the long-term ramifications of ever-changing environmental research and the modifications required might result in additional costs. Finally, the technical capabilities of the hospital’s location must be examined since they might influence how environmentally friendly the hospital can be.

Though green SCM and its application to hospitals have not been extensively researched, there appears to be a significant promise for its adoption and use. While medical institutions have little possibility to influence their upstream supply chains, they may optimize their operations and reduce waste generation. Furthermore, both public and commercial hospitals have incentives to do so, such as lower long-term expenditures. Considering this, the present study shows that green SCM adoption is a process that cannot be efficiently carried out in a solitary institution. The environment in which it operates must be suitable for the purpose, which necessitates the presence and accessibility of various waste recycling facilities, among other things.

During this investigation, the researchers collected both quantitative and qualitative data by analyzing descriptive papers and statistical data analysis studies. A review of the literature aided in identifying existing procedures that both institutions that are the focus of this study are employing to adopt GSC and satisfy international standards. As a result, this study was undertaken to utilize the desk research approach, in which literature on the issue was collected and analyzed, with a primary focus on the history of SCM practices in healthcare systems in both states, Turkey and the US. The empirical findings were based on the study of both qualitative and quantitative data. Both descriptive and explanatory studies were employed to reach this purpose. The decision to do mixed methods research is supported by the necessity to conduct high-quality research that tackles the risks.

Introduction

Introduction

In recent decades, the level of environmental awareness among the public has increased significantly in relation to different sectors, including the healthcare industry. The health care expansion effect has led to increased hospital operations and increased sensitivity to hospital relatedness to sustainable management, among other environmental-related concerns. These changes, among other issues, have triggered a globalized effort that has led to the establishment of global standards to address concerns that link to global environmental management issues in different nations (Standards: ISO standards are internationally agreed by experts 2020). Various hospitals in Australia and other countries have tasked their agencies that relate to public health, such as the Australian department of public health, to ensure enrolments of the international standards such as ISO 22870, ISO 151197, and ISO 9001 in different health care industry operations. The application of the ISO standards ensures effectual quality service delivery satisfies all stakeholders’ preferences (International standards 2020). The application of the international standards, however, follows different actions to ensure success in the health care industry.

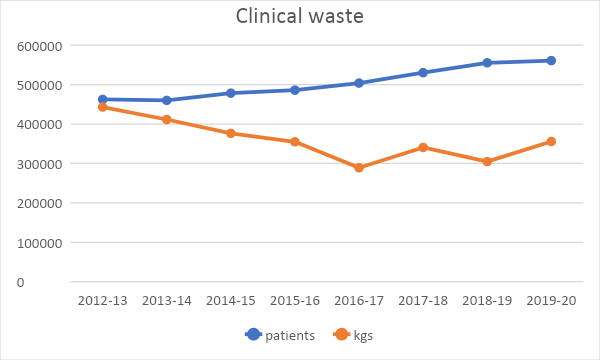

This research is an empirical study of the supply chain management SCM practices from two hospitals: one located in Turkey and the other in Australia. The first hospital is the Australian Hospital A that has 571 beds and helps over 500,000 patients, while the second study subject is the Derindere hospital, with 386 beds serving 10,000 patients. During the course of this study, the researcher will collect and interpret information about the SCM and sustainability practice in both facilities using the case study method. The goal is to use quantitative and qualitative methods to collect information about the hospitals’ SCM practices, green objectives, and the impact of these factors on their operations.

In line with increased environmental awareness, administrators are tasked with significant roles that involve making critical decisions that alter different hospitals’ operations. In line with other environmental demands, the administrators have also employed critical approaches to supply management while refocusing on creating green supply chains (GSC) to reduce energy and resource consumption, address the lack of recycling, and improve waste management (Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). The change necessary to address the problem involves altering hospital functional processes to rhyme with the systematic approach applied globally to improve hospital management and create other options that will result in sustainable management. The changes aim at critical issues started in international standards operations that involve customer satisfaction and continuous provision of high-quality products regardless of organizations’ scope of practice (ISO 9001:2015 2019). The significant changes are equally linked to environmental factors, which enhance environmental performance and achieve environmental sustainability objectives (ISO 14001:2015 (en) Environmental management systems — requirements with guidance for use 2020). In this context, hospitals are identified to face the challenge of increased expenses for using medical and non-medical supplies, and they are seeking ways to reduce both costs and the negative impact on the environment.

Despite the focus of modern organizations on applying the principles of green supply chain management (GSCM), the healthcare sector across the globe can be viewed as being at the initial stages of transitioning to GSCM. The reason is that hospital management has only recently begun to develop strategies that correspond with the requirements of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 (Gerwig 2015). The key requirements of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 involve developing hospital performance practices that incorporates the needs of stakeholder plus incorporating the needs of the changing environmental demands that do not alter the efficient operations of any organization (ISO 14001:2015 2020; Noviantoro et al. 2020). The recent implementation of the ISO standards has led to improved hospital operations including increased focus on patient operation promoted by employment of internal processes improvement decisions that promotes increase efficiency levels in hospitals operations. As Noviantoro et al. (2020) state, the integration of the ISO standards in GSC policies in different hospitals has involved this process of developing new operational principles that cater for the enhancing the environment sustenance level and in consequence improving the operational efficiency levels in different organizations.

In order to address the said situation, some hospitals in such countries as Australia and Turkey chose the principle of GSCM. Thus, managers from the healthcare industry have implemented GSC according to international based standards. The managers aim to increase environmental performance levels and improved hospital abilities to meet customer needs in providing its services (ISO 9001:2015 2019; ISO 14001:2015 (en) Environmental management systems — requirements with guidance for use 2020). These changes ensure guaranteed environmentally friendly management approaches (Stoimenova, Stoilova & Petrova 2014; Toprak & Şahin 2013). In this context, it is important to research what challenges were faced at the stage of implementing GSC in hospitals in both countries and what benefits were achieved. This chapter presents the background for the study, the rationale for this research, aims of the study, research questions, the contribution to theory and practice, the statement of significance, and a conceptual framework.

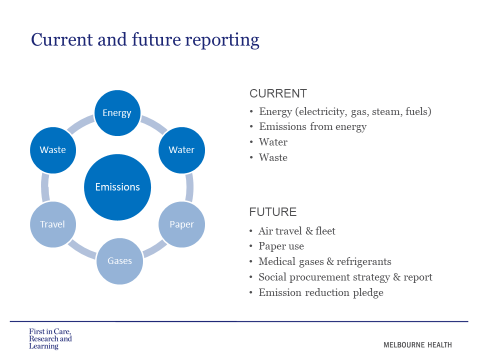

Environmental issues are a concern for the global community, including the governments and the general public. For example, the Doctors from Australia (no date, p. 1) report that “climate change is a health emergency that is contributing to deaths and life-threatening illness” and meeting the emissions standard outlined in the Parisian agreements Australia will have to reduce its emissions by 7.6% each year. This is a substantial reduction that requires efforts from the public, businesses, and the government, and the latter in particular will advocate for the change by issuing policies and prompting businesses and public service providers to change their operations and the management of their supply chains to address the target reduction. Doctors from Australia (no date, p. 1) also state that “net zero emissions by 2030 from the Australian healthcare sector, while desirable, are unlikely to be achievable due to the lack of a ‘road map’ and consistent measurement of carbon emissions to track changes.” Therefore, there is an emergent need for research and practice recommendations that hospital managers will be able to apply to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions and the environmental impact of their entities to help the state achieve the goals outlined in the Parisian agreements and to address the global environmental changes. Therefore, this paper makes a contribution to the understanding of how the ISO standards can be applied to rapidly enhance the efficiency of green practices used by hospitals and their management.

The specifics of the hospital supply chain management are linked to both the constraints of the healthcare systems and the legal frameworks under which the SCMs have to operate and the economic system that prevails globally. According to Moons et al. (2019, p. 205), “the medical supply costs constitute the second-largest expenditure in hospitals, after personnel costs.” This means that SCM is among the essential elements that allow the healthcare facilities to deliver the services of care to the patients, making it important to consider the recent trends and directions of development for the SCM. A sustainable healthcare supply chain can be achieved by combining the triple bottom line, industry 4.0, and the corporate social responsibility statements (Dau et al., 2019). Hence, hospitals have to maintain a balance between ensuring that the SCM practices they use do not endanger the patients, which in many cases means that they are required to work following strict standards, such as have uninterruptable energy sources within their facilities or work with suppliers who have obtained a state verified certification for their products and the recent trends towards environmentally friendly practices. Phillips (no date) states that the latter is the outcome of the Circular Economy, which is the system where the focus is not on merely the production of goods and services but also on combatting the global challenges.

Climate change is one of such challenges since it is affecting all the nations and will continue to impact the next generations and because the companies and facilities operating in different parts of the world are all contributing to this environmental change. Apart from this, the Circular Economy deals with the issues of losing the planet’s biodiversity, excessive waste, and pollution (Phillips, no date). In contrast to this, the linear economies, under which the majority of the businesses and SCM systems currently operate, are designed to produce items that will eventually become waste without regard for what will happen to this product after it has fulfilled its purpose and how the process of procuring raw materials and operations of the production facility contribute to the pollution and greenhouse emissions. Although linear economies have successfully satisfied the demand for products and services in the past, climate change and environmental damage prompt managers and policymakers globally to change the way they approach production and SCM in particular and adopt strategies consistent with the Circular Economy principles.

The SCM practices that align with the Circular Economy system have to consider the broader consequences of production and product use. Invernizzi et al. (2020) define the following methods that can be used under this principle: reuse, refurbish, recycle, remanufacture, establish a closed-loop system, and use minimum resource inputs. However, for hospitals, due to the safety and sanitation standards, not all of these methods can be used. According to WHO (2018), the coverage of the closed-loop economy practices for the healthcare facilities and suppliers has been limited, suggesting that this industry still requires a plethora of research and evidence-based practices implementation and testing to establish a clear framework that balances the healthcare standards and environmental consciousness. Moreover, a broad set of stakeholders is involved and affected by the attempt to transform the healthcare system towards one that is sustainable. WHO (2018, p. vii) states that these are “intergovernmental organizations, governments of WHO Member States, the public sector, the business sector, non-governmental and civil society organizations, the research community, the mass media, and the general public.” Form this; one can conclude that the issue of environmental practices application in healthcare is important since it impacts a broad range of people and organizations, and considering the underlying implications of why the Circular Economy has emerged, this issue is meaningful not only for people who use healthcare services but also for the future generations who will be affected by the depleted resources, change in the climate, and pollution.

The issue of SCM using green practices has broader implications and, ideally, should be addressed at the initial stages of developing a project for a future healthcare facility. Dau et al. (2019) examine the potential barriers and established business practices that might become barriers to the transition towards the circular economy in healthcare since suppliers in GSCM systems still have to maintain their profitability and operate under conditions that make their businesses viable. For healthcare institutions, the integration of the sustainability practices has to be reflected in the corporate social responsibility statements of these facilities because they show the commitment of these organizations towards transitioning to the better use of resources. Moreover, Dau et al. (2019) argue that apart from the SCM practices that support the immediate needs of the hospitals, the executives should also pay attention to the supply of the materials and cooperation with contractors when building new facilities, such as new hospital wings or units. This attention is required because new technology, such as the use of solar panels and electricity and light resources on the stage of designing a facility, can significantly affect the future demand of this facility for the things such as electricity or light or waste management, which are a part of SCM. The present study can serve as a blueprint for future hospital projects because it will outline the practices that are currently employed by two hospitals that have the ISO certifications, meaning that the structure and the facilities of these buildings can be developed considering the future resource use.

The triple bottom line, as one of the components of a sustainable supply chain, is the assessment of the impact that the business has on the environment. As opposed to the traditional concept of a “bottom line,” which is solely based on the income that a particular company can generate, the triple bottom line also considers the stakeholders and the broader implications of the company’s operations, which is also applicable to the private hospitals and healthcare suppliers (Miller, 2020). This concept consists of three elements: “profit, people, and the planet,” which means that a successful business, under the triple bottom line model, has to earn revenue, have a positive impact on the customers and the community where it operates, and use practices that do not harm the planet (Miller, 2020, para. 5). From the viewpoint of the hospitals, this approach means that they should account not only for the patients whom they help as part of their daily operations and the revenue versus expenditures that result from these but also the broader implications of how the resources that the employees use and the patients need are affecting the environment.

Based on this assessment of the Circular Economy and the triple bottom line, one can assume that the management of the supply chains in the hospitals has to change eventually since there is a global trend among businesses to adjust the practices towards the ones that will provide the owners not only with the profits but also will not affect the environment negatively. These changes are inevitable also due to the public’s awareness of the environmental issues and their impact on the planet since, according to Phillips (no date) and TORK (2019), 94% of patients care about the hospital’s sustainability practices. Therefore, these patients will select the facilities that have a corporate social responsibility strategy and which voice their SCM practices and how that help preserve the planet and the climate. This matters in particular for the countries with private healthcare, one of which is Turkey, where the healthcare system is a mix between private and public facilities, and the patient is essentially a consumer whose preferences will affect whether this entity will gain profits. For public hospitals, the issue of patients’ awareness of the environmental issues and GSCM practices is linked with the allocation of insurance payments because individuals have the opportunity to choose a provider. Therefore, this paper explores the specifics of GSCM not only due to the trends towards the sustainability and environmental friendliness that prevail in the global economy, but also because of the increasing attention from the general public towards the specifics of corporate social responsibility, resource use, and SCM practices at a given facility. Therefore, the results of this study will provide hospital managers with insights into the issues of green supply chain management and the best ways of implementing the ISO sustainability standards into a healthcare facility’s operations, regardless of whether the hospital operates as a public or private entity.

GSCM is a concept that emerged fairly recently, and it relates to the suppliers adjusting their practices, such as production methods, materials they use, the in-house energy consumption levels to reduce the amount of carbon footprint and the waste that is normally generated by these businesses entities. The overall goal of GSCM, not only in the context of healthcare, is to help address concerns beyond the mere satisfaction of the demand for a certain type of healthcare product, such as syringes, and instead, satisfy the demand in a way that minimizes the impact of this process on the environment and helps preserve the planet.

The reason why this study examines GSCMs in the context of hospitals is that they are among the most significant contributors to greenhouse emissions globally, and in Australia and Turkey in particular. Therefore, by enhancing the understanding of how the two hospitals already use GSCM developed under the ISO standards, one will be able to create recommendations for all healthcare entities that will provide effective and proven methods of changing the supply chain management to the type of system that is both effective in satisfying the demand for the healthcare products and services and is not affecting the environment negatively, as the existing systems do.

ISO was selected as a standard for this case study because it is an internationally recognized framework for regulating the different elements of business operations that are used internationally. Hence, the ISO standards selected for this paper allow examining the consistency of applying the SCM and GSCM practices across varied settings. The benefit of using an ISO standard is its applicability across different healthcare settings that will allow utilizing the results of the present study for the improvement of the management of the hospitals in countries beyond Australia and Turkey. Moreover, this study will help examine whether the ISO standard for GSCM is adequate for setting up an SCM system that will operate both efficiently from the viewpoint of business operations and which will address the environmental concerns of the hospital’s greenhouse emissions and resource use.

The main concerns regarding the “environmentally unfriendly” practices of the healthcare facilities include generating large quantities of unrecyclable waste, emitting pollutions, and using nonrenewable energy not efficiently. Despite the fact that authors and the general public have raised concerns and discussed the environmentally damaging practices that are routinely applied by the hospitals, not many changes are made by these facilities to this day. An example of such discussion is a report by PA Consulting, written by Phillips (no date), who argues that hospitals consume large quantities of nonrenewable energy, which is supported by the research from Yale University where healthcare facilities were found to be the second-largest energy consumers in the United States. In terms of the carbon footprint ratio, they account for 10% of the overall emissions in the state, and the amount of carbon dioxide they emit has increased by almost 30% between 2006 and 2016 (Phillips, no date). Although these findings are relevant for the United States, one can generalize the numbers to describe the current state of emissions by healthcare entities in other developed nations as well.

The present study will be a significant contributor to understanding the current GSCM practices in the context of the healthcare environment and will serve as a guide for hospital managers who want to implement the ISO standards into their operations but who are not sure how these standards work in practice and how they align with the day to day operations of a healthcare facility. Some general recommendations that Phillips (no date) outlined include updating the procurement management strategies, such as enhancing the waste management strategies. This can be achieved through partnerships with medical device suppliers to develop alternatives for single-use devices. Such partnerships can help the manufacturers dress the issues associated with infection control by developing protocols and control systems that are directly monitored by their partner hospitals. Additionally, Phillips (no date) recommends applying recycling in non-hygiene-related areas, such as the management and delivery of food across the hospital. These simple steps can help improve the hospitals’ operations in regard to their environmental footprint; however, these are theoretical developments. This paper addresses the lack of case studies and other related developments that would guide the facility managers in the direction of evidence-based sustainability.

Supply chain management, in general, is a complex subject and the integration of green practices makes it even more challenging for healthcare managers. According to Moons et al. (2019, p. 205), “a well-defined supply chain strategy is needed for aligning internal logistics processes and controlling supply chain costs in a hospital.” Moreover, in such supply chains, measuring the performance loss points and parts of the logistics where improvements can help save costs become essential. Moons et al. (2019) define two supply chain domains that require attention from a GSCM perspective: the delivery of items to the hospitals and the distribution of these to the points of care. Moreover, the ethical aspects of healthcare imply that the providers distribute not only the physical goods required to provide the services, but they are also responsible for the information flows that are directed at a patient.

Finally, the justification for using the ISO standards as opposed to examining the general practices of the hospitals that are under the sustainable category should be provided. First and foremost, this study aims to help healthcare managers globally, in line with the Circular Economy theory, where entities have to account for their impact on the global society and the planet. Hence, there is a need to use a set of standards that could be applied across different nations as opposed to focusing on the sustainability practices that are outlined in the regulations of the Australian or Turkish governments. Secondly, the use of ISO and the comparison of the two hospitals in different states can make it possible to healthcare managers from public and private sectors to find insights for themselves, since there are differences in the way the public and the private entities operate and in particular how they manage their suppliers. Hence, this case study will be applicable to different healthcare systems, which will make it more universal. Finally, based on the findings, the authors will propose an improved framework for the ISO standard and some recommendations for hospitals that want to implement these. This is necessary to address some inconsistencies and the areas of the unknown in relation to how the ISO is implemented in real life. Hence, the results of this study should contribute significantly to the research and practice in the area of SCM sustainability for hospitals, both private and public.

As for the gaps in the existing literature, the main issue is the lack of empirical studies that would show the benefits and downsides of applying the green SCM in the healthcare industry sector. For example, there are theoretical papers from 1982; however, to this day, there are few case studies or research papers that managers can use to learn about the implementation of green SCM (Asgari et al., 2016). Moreover, Agi et al. (2021) and Haiyun et al. (2021) also point to the problem of not having data or best practices that would guide the management towards the effective implementation of GSCM.

This research has allowed one to determine some of the benefits of greening in the long run. For example, green SCM is beneficial for waste management, which means that the hospital can reduce the amount of recyclable and non-recyclable trash. Additionally, the green wing allows saving energy resources, which is also beneficial for the financial management of the facility.

UN-SDG goal addressed by this research is number 11, “sustainable cities and communities” (UN, no date). As hospitals, whether public or private, are essential institutions for communities, ensuring that their operations are efficient and do not harm the environment becomes essential. COPD30 strives to affect global climate change, and goal four of this initiative is the following: “accelerate action to tackle the climate crisis through collaboration between governments, businesses and civil society” (‘COPD30′, para. 4). Hospitals are a part of civil society, and the management of these facilities has to align with the goals for minimizing the impact of climate change. Therefore, the motivation for this research is the need to gather and analyze empirical data that hospitals’ management can use to effectively implement the GSC management practices.

Context Chapter

The following paragraphs will provide the context for this research and the issue of sustainable hospital management and greening of SCM. On the one hand, sustainability and green practices within the SCM systems promise an enhanced way of managing the suppliers, the one that does not harm the environment while providing the necessary supplies on time and in required qualities. On the other hand, there is a risk of making the SCM system costly and ineffective when focusing on the greening of supply chains and omitting the business aspect of operations, which is important for hospitals, both private and public.

The current practices of supply chain management of the hospitals imply the use of supply chains that allow the hospitals to save money while receiving the products and services they need to operate (Fahimnia et al., 2018). Little attention is given to the issue of sustainability and the use of green practices in general, despite the fact that the notion of GSCM has existed for over thirty years (Fahimnia et al., 2018). Moreover, the main reference for GSM currently is the ISO standard since few research papers or case studies exist that would explain the best practices of GSCM. Hence, many healthcare facilities have already begun to transform their SC to comply with the ISO 9001-2015 standard, but the lack of research and empirical data makes it challenging to do this effectively.

Another issue is the balance between creating an effective supply chain, which is the one that allows receiving the resources that the hospitals’ employees require to provide the healthcare service with the green practices. For example, Fahimnia et al. (2018, p. 129) note that “both greening and buttressing can be costly, green supply chains are most sensitive to disruption, robust supply chains have strong long term benefits, and buttressing a green supply chain is a good investment.” Hence, despite the positive effect on the environment, GSC management remains expensive and not as effective as the traditional SCM practices. Moreover, greening practices are “requiring suppliers to be green and requiring additional greening investments may result in having fewer suppliers, influencing overall SC robustness,” which means that green supply chains are not equally effective for all industries (Farhime et al., 2018, p. 129). Therefore, this research helps determine whether GSCM is an adequate practice for private and public healthcare institutions.

Institutions and business organizations are facing pressure from the stakeholders to implement sustainable and green practices into their operations. Fahima et al. (2018, p. 129) state that “new environmental regulatory mandates and tighter sustainability reporting regulations” are the evidence that organizations have to adopt green practices into their operations. In addition, the COPD30 and UN-SDG initiatives draw the public’s and government’s attention towards the enhancement of the SCM and the need to focus on sustainability and the reduction of the environmental impact of human activities, which includes hospitals as well. Thus, this research helps managers explore the effective ways of managing the green SC and have a balance of robustness and environmental sustainability.

Thus, these two government and private hospitals require an in-depth study because their management has already begun the process of implementing GSM, and their examples, including the positive and negative effects of greening, can help avoid the potential mistakes for other healthcare facilities. Ther experience in managing green SC can help other healthcare institutions implement the same practice considering the experience, mistakes, and best practices described in this paper.

Research Background

The application of effective management practices in hospitals plays a key role in contributing to the healthcare industry’s better performance. Studies indicated that the adoption of the most efficient and evidence-based management practices in hospitals guarantees reductions in patient mortality rates, improvements in patient outcomes, enhancements in providing care, and positive changes in operations and workforce’s activities (Dobrzykowski et al. 2014; Machado, Scavarda & Vaccaro 2014). In this context, effective management practices include techniques associated with organizing the work of staff, delivering care, distributing funds, using equipment, and promoting retention, among others (Chiarini 2015). This section presents the discussion of healthcare management practices adopted in hospitals of Australia and Turkey, focusing on the review of SCM principles followed in the healthcare sector to provide the background for the current research

Healthcare Management Practices in Hospitals in Australia

The healthcare system of Australia includes both public and private sectors. The annual healthcare expenditure for this industry in the country is about $AU100-110bn (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). The public sector represents about 70% of the industry in terms of provided funding covered by the federal government (40% of funding) and state governments (60% of funding). Thus, about 30% of the industry are privately funded (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012). Public hospitals remain most popular among Australians because of the high quality of provided care, and about 60% of patient admissions are addressed to public hospitals in Australia (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). In spite of an appropriate budget adopted for hospitals in Australia, the quality of the work of a healthcare system depends on effective management. The problem is that healthcare costs increase each year and certain changes to demography have led to developing challenges for managing healthcare facilities successfully and providing high-quality services to implement working management practices.

From this perspective, managers in Australian hospitals work to adopt specific practices to improve, maintain, and effectively monitor healthcare operations, workers’ performance, people management, care delivery, quality management, waste management, and the work of a supply chain. In Australian hospitals, much attention is paid to guaranteeing the high quality of provided services and ensuring that the length of patient stay is appropriate, and spent costs are reasonable (Agarwal et al. 2016). In order to achieve these results, managers improve used protocols, promote the utilization of the most efficient clinical practice guidelines, focus on the most effective organizational practices, and change hospital layouts to address patient flows (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). In addition, they introduce advanced technologies to provide care for more patients and exchange knowledge and data, implement practices to reduce expenses, and focus on innovative and cost- and resource-efficient management approaches (Agarwal et al. 2016; Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012).

In order to build accountability in Australian hospitals, managers and administrators focus on implementing new systems for working with material and human resources, evaluating performance and outcomes, ensuring sustainability, and guaranteeing high-quality care. For this purpose, healthcare administrators change their approaches to addressing a community’s needs and patients’ expectations, managing waste, developing supply chains, and monitoring performance (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Rodwell & Gulyas 2013). As a result, levels of employee commitment and the quality of care in Australian hospitals are comparably high according to recent statistics for the industry (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). Therefore, it is possible to state that modern healthcare management practices adopted in public and private hospitals of Australia are oriented not only to the improvement of patients’ treatment but also to the use of most cost-efficient approaches in their practice.

However, not all Australian hospitals are managed effectively to address patients’ needs, stakeholders’ interests, and save costs. The adoption and work of management practices in the healthcare industry depend on various factors, including managers’ leadership, the type of implemented practices, management areas covered during change processes, the staff’s response, and specifics of cooperation with suppliers. From this perspective, administrators in the most successful Australian hospitals tend to pay much attention to managing their operations and applying SCM principles (Agarwal et al. 2016; Böhme et al. 2014). The choice of the most effective approaches in this case is based on hospital-specific features that determine paths selected by managers in the healthcare industry to achieve higher outcomes for patients and decrease associated costs.

Large Australian hospitals with more beds and patient flows usually demonstrate more strict management, effective performance, and high-quality care because of the adoption of the most efficient managerial practices appropriate for the healthcare industry. Nevertheless, these hospitals, which often belong to the public sector, also face the most critical challenges and barriers to decreasing costs, balancing expenses, and avoiding the negative impact on the environment and community because of their activities (Böhme et al. 2014; The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). Moreover, supply chains in the healthcare industry in Australia differ significantly from other sectors. All these aspects influence Australia hospitals’ necessity to revise their policy with the focus on strategies, methods, and SCM improvements in these facilities and contribute to sustainability and corporate responsibility.

Healthcare Management Practices in Hospitals in Turkey

In Turkey, the healthcare industry is accounted for about 6% of the country’s GDP, and it is represented by public and private sectors (Polater, Bektas & Demirdogen 2014). However, in spite of paying much attention to funding this industry, there are still management issues that can be observed in different types of Turkish hospitals. The healthcare industry is constantly growing and developing in order to address national health goals, and as a result, it is oriented to adopting changes and using a variety of efficient healthcare management practices. Technological improvements and enhancements in the quality of provided services are typical of the Turkish healthcare sector (Akdaǧ 2015; Erus & Hatipoglu 2013). Although much attention is paid to innovation and changes, common issues include the reference to ineffective managerial practices and processes, the inappropriate utilization of resources, the use of outdated systems for sharing information, the use of ineffective cost distribution and control strategies, as well as the application of inefficient waste management (Akdaǧ 2015; Erus & Hatipoglu 2013; Polater, Bektas & Demirdogen 2014).

From this perspective, it is possible to state that healthcare management practices applied in Turkey’s hospitals are most effective when they are oriented to change management. With that said, this direction does not resolve the matter entirely, and other measures will also need to be applied to maximize performance. According to Özkan, Akyürek, and Toygar (2016), there are problems with managing healthcare personnel, organizing effective healthcare logistics, and controlling the work of supply chains to reduce costs and address the inefficient use of resources. Camgöz-Akdağ et al. (2016) also agree that healthcare management practices in Turkey require improvement. The focus should be on integrating strategies and techniques that can help healthcare providers and administrators reduce costs and funding and change the approach to using resources, and achieve better outcomes for patients. This aims carter the demands of international standards provisions that requires enhancing organizational operations to carter for management inefficiencies that alters the ability of the hospital to meet higher level of customer satisfaction through effective application of the system including making process improvement to conform to statutory and regulatory requirements Thus, administrators in Turkey’s hospitals have achieved significant positive results in implementing innovation and change in their organizations. However, the basic healthcare management practices still need to be improved and developed.

The healthcare sector’s focus on innovation and change is the adoption of national policies directed towards the promotion of the universal health coverage for all citizens in Turkey among other initiatives (Akdaǧ 2015; Erus & Hatipoglu 2013). From 2002 through 2012, Turkey’s healthcare industry experienced significant changes in the context of realizing the principles of the national health transformation program. On its path to providing universal health coverage, Turkey achieved the improvement of the nation’s health status, decreases in infant mortality rates, and increases in patient satisfaction. The overall access to healthcare increased for different categories of the country’s population, and this aspect created more challenges for organizing the work of healthcare personnel in hospitals (Akdaǧ 2015; Erus & Hatipoglu 2013). Despite the fact that updating health information systems, reorganizing resources in healthcare facilities, redistributing costs, and improving supply chains were tasks required for completing in the context of the Health Transformation Program, there are still barriers to achieving these goals.

Moreover, it is important to note that changes in the country’s healthcare industry have led to attracting more healthcare practitioners to public hospitals because of increased incentives. As a result, approaches to organizing specialists’ work and using resources have been changed as SCM principles were followed inappropriately in many cases (Akdaǧ 2015; Erus & Hatipoglu 2013; Özkan, Akyürek & Toygar 2016). Thus, inefficiency in the work of public hospitals of Turkey can be observed even today in spite of efforts made by healthcare administrators to address the problem. From this perspective, it is possible to state that healthcare management practices used in Turkish hospitals are developed to address the policies associated with health transformation program that have been realizing in the country during a decade. However, there are still problems with integrating practices that can reduce costs and improve the use of resources without compromising the quality of care.

Rationale for Research

The practical application of green SCM approaches in the healthcare industry is still almost unstudied in contemporary literature despite the current interest of researchers in investigating this problem in different sectors, including healthcare. In spite of the fact that many hospitals in different countries choose to transform their SCM into GSCM to reduce waste, focus on recycling, and eliminate a negative impact on the environment, additional research is still required in this field (Chakraborty & Dobrzykowski 2014; Kovac 2014). Moreover, scholars and practitioners have to pay attention to the fact that those practices that are used by managers to make their supply chains green require further investigation in a specific healthcare industry. Furthermore, the national factor is also important in this context because GSC strategies and practices selected by healthcare managers in various countries differ significantly.

As a result, it is assumed that the experience of hospitals in Australia and Turkey on their paths to building GSC is different, with the focus on certain barriers, challenges, advantages, and disadvantages associated with this process. The problem is that more research is required to examine how hospitals can successfully apply green SCM practices to address the idea of sustainability and reduce their environmental influence with reference to specific case studies. Moreover, research is also required in order to understand how the application of ISO 14001 and ISO 9001 can influence the process and lead to developing GSCM in this or that facility (Muzaimi, Chew & Hamid 2017). The ISO application provisions demands for innovative process change on the current organizational operations that carter for the current customer needs and other current environmental demands (Ferreira, Poltronieri & Gerolamo 2019). Although discussing supply chains in the healthcare industry researchers often refer to ISO 14001 and ISO 9001 standards, there is still no appropriate evidence to state that the application of these standards is directly associated in hospitals with their realization of GSCM.

Certain practices are important to be implemented in Australian and Turkish hospitals to improve SCM to overcome challenges associated with high costs, disintegrated processes, and resource-consuming operations. As a result, the rationale for conducting this study is that there is the lack of literature on comparing the experience of hospitals from different contexts regarding the development of GSC. Moreover, there is also the lack of literature on discussing the application of ISO 14001 and ISO 9001 in this area. Finally, more recommendations for practitioners are required to be formulated as a result of this study. It is important to investigate how the application of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 standards can contribute to building strong integrated GSC based on dyadic relationships in Australian and Turkish hospitals. It is also critical to compare the findings for two national contexts using a mixed-methods case study design.

Aims of the Study

First, this research aims to evaluate and describe the specific connection between the application of green SCM principles and successful compliance with the ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in certain selected hospitals in Australia and Turkey. Further research should examine how hospitals in Australia and Turkey can apply green SCM and ISO 14001 and ISO 9001 and integrate them into its daily practices because the trend of greening practices is comparably new for the healthcare industry all over the globe (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012;Camgöz-Akdag et al. 2016). The second aim for this research is to determine and explain the procedures that are necessary for applying effective greening strategies that comply with ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in the healthcare industry of both countries. Finally, the third aim is to compare and contrast processes of greening supply chains with reference to ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in the selected hospitals of Australia and Turkey to conclude which approach is more environmentally friendly.

These aims reflect the need for examining GSCM strategies in the selected hospitals to provide the background for additional research on the topic, determining how these case studies are representative of greening practices in some hospitals of Australia and Turkey. The research does not aim at comparing the hospitals’ achievements in greening supply chains based on the type of ownership, and the focus is on comparing practices in different national contexts. The aims address critical issues determined for Australian public and Turkish private hospitals, which have grappled with the problem of increased healthcare expenditures and the negative impact of management on the natural environment due to the growing number of patients, along with the increased volume of waste.

Moreover, these processes may be connected with increasing activities in hospitals over the past decades (World Health Organization 2014). The problem is that, in Australia and Turkey, public and private hospitals only start focusing on GSC initiatives, and the overall process of shifting standard managerial processes to this specific greening practice is rather complex and problematic (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). The complexity of health care sector operations continues to intensify in the current period. And as noted in the ISO provisions, hospitals are to ensure that current issues are addressed considerably and more innovative approaches are used to ensure successful implementation of environmental management processes (Noviantoro et al. 2020; Sepetis 2019). Such innovative measure includes the management policies applied by different organization in the implementation of green supply management.

Consequently, at this stage, supply chains in Australian and Turkish hospitals can be viewed as mostly disintegrated. The reason is in faced problems with information sharing, controlling processes, and planning interactions with suppliers and customers. Social costs that are associated with these challenges are high because they affect the quality of proposed services and care (Chakraborty, Bhattacharya & Dobrzykowski 2014). In order to address these problematic questions, the current research will be built on a new framework that is based on the explanation of the influence of innovative greening practices on the traditional organization of business and logistics management processes in the healthcare industry.

This study used a TOE framework to address the main issues with the implementation of GSCM from the organizational perspective. The objective of this research is to address the literature gap on GSCM practices in healthcare, which is the lack of studies that would explore the practice of implementing the GSCM standards aligning with ISO 14001 and 9001 in the healthcare system. The current literature either explores the theory of GSCM or focuses on statistical data. Moreover, only a few studies explore GSCM within the healthcare system, and no study was found that compares the application of GSCM to public and private institutions. Therefore, by analyzing the application of GSCM practices in Australia and Turkey, the researcher aims to create a case study that healthcare institutions’ managers can use to implement GSCM in their facilities effectively.

Moreover, the analysis of the literature shows that the input of stakeholders is essential for the proper implementation of GSCM. The stakeholders, such as the hospital’s patients, community members, policymakers, and international organizations, are the ones pressuring these healthcare facilities to implement greener practices into their operations.

Research Questions

Hence, this case study will serve as a reference point for managers who want to understand the needs of their stakeholders when implementing GSCM. Hence, the research question for this case study analysis is the exploration of the expectations and the effects of implementing GSCM practices on hospitals. The case study is written using data collected from two hospitals, one private and one public, to showcase the management differences of the two approaches. This study examines specific cases related to adopting SCM practices in hospitals of Australia and Turkey and their success in following ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 standards. In order to address the purposes and aims of the study, it is necessary to respond to the following main research question:

Research question: what are the effective strategies for implementing a GSCM management strategy that hospital managers can use, and what potential limitations of GSCM will they face?

Sub-Questions:

- What is the significance of greening hospital supply chains in Australian and Turkish hospitals?

- How can SCM changes in hospitals, both public and privately owned, of Australia and Turkey be promoted effectively?

- Why is the application of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in the context of integrated GSCM appropriate for Australian and Turkish hospitals?

- What integrated GSCM procedures, corresponding with ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015, are applicable to healthcare sectors in Australia and Turkey?

ISO 9001 and ISO 14001

The ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 standards are used by the International Organization for Standardization. The former is the better-known of the two, as it covers the foundations of a quality management system. Most businesses have recognized the utility of such a framework, and it has become standard to create one. The ISO offers certification that confirms an organization’s compliance with the ISO 9001 standard, which has helped establish its reputation. ISO 14001 is a similar standard to ISO 9001 that sets out the basic standards for creating an environmental management system. It can also be certified to, but, since it is a newer development, as indicated by the higher family number, it is not as popular as its quality-related counterpart. With that said, certification in either standard can provide the assurance that the organization’s systems are based on a sound design approach to its employees and stakeholders. Moreover, the basic structure can serve as a foundation for the development of a more advanced green framework that takes the context of the organization into consideration.

Contribution to Knowledge

This study significantly contributes to both theory and practice related to the topic of implementing GSC in the healthcare industry. The reason is that the lack of research is currently observed regarding this issue, and there are many aspects to examine and discuss while referring to the contexts of Australian and Turkish hospitals. Specific theoretical contribution and practical contribution will be considered and discussed below.

Theoretical Contribution

The development of modern healthcare sectors in both Australia and Turkey is rapid due to significant increases in numbers of patients requiring treatment and new functioning hospitals. However, the problem is that such increase in the volume of the healthcare sector operations directly affects the condition of the natural environment in Australia and Turkey (Agarwal et al. 2016; Akdaǧ 2015). Therefore, a specific impact of healthcare operations on the natural environment has become a subject of scientific and management interest that requires its further discussion and analysis. The issue is specifically related to the situation with Australian hospitals because the national government emphasizes the implementation of advanced greening techniques to minimize the negative impact of the healthcare industry on the natural environment (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Böhme et al. 2014).

The similar situation is observed in Turkey, where the government published a series of regulations in order to improve waste management processes in different sectors, including the healthcare sector (Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). To address the negative impact of the absence of recycling procedures and effective waste management techniques, companies and international organizations develop environmentally friendly approaches to management, such as GSCM, that is the transition from traditional supply chains to eco-friendly ones (Özkan, Akyürek & Toygar 2016). As a result, it is essential to understand the role of integrated green SCM in greening healthcare business procedures, along with possible benefits, when considering public and private medical facilities in Australia and Turkey.

From this perspective, this research will add to the scholarly SCM literature in healthcare and GSCM in Australian and Turkish public and privately owned hospitals. It is possible to state that, currently, the identified subject of interest lacks the detailed investigation, discussion, and analysis, especially in terms of comparing adopted green SCM practices in the hospitals of Australia and Turkey. Therefore, the proposed research seems to have theoretical significance as the planned study will also discuss the application of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001- 2015 in the context of the healthcare industry as the framework for developing GSC (Agarwal et al. 2016; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016; Özkan, Akyürek & Toygar 2016). The analysis of potential drawbacks and benefits connected with arranging integrated green SCM based on the requirements set by these two standards in Australian and Turkish hospitals will also add to the theoretical significance of the study.

Practical Contribution

There are many studies on specifics of applying ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in healthcare organizations of different countries, but the limited research on the situation in Australia and Turkey is present. It is important to focus on how these standards can be used in hospitals over the globe. In the context of adopting the ISO 14001-2015 standard, it is expected that organizations will be able to reduce their waste, contamination of air, water, and soil, eliminate costs, and avoid the use of hazardous materials (International Organisation for Standardisation 2015). Furthermore, the application of the standard in hospitals is associated with decreasing the possibility of environmental accidents and enhancing performance because of decreased numbers of pollutants in the environment (Chege 2012). Therefore, while applying ISO 14001-2015, organizations become able to determine what environmental impact their operations have and how it can be addressed in terms of controlling activities, using resources, and manipulating inputs and outputs.

The problem of organizing efficient GSC in Australian and Turkish hospitals to overcome the issue of polluting the environment and improving waste management is practical in its nature. The analysis of GSC in healthcare industries of these two countries allows for determining the most effective approaches to forming supply chains in order to achieve the highest outcomes for hospitals applying ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 standards, as well as for their communities which involve a move to meeting current community needs and other environmental management demands.(Muzaimi, Chew & Hamid 2017) From this point, the practical contribution of the study is that its results will help managers and administrators in public and private hospitals in Australia and Turkey to identify and overcome possible complexities or challenges that are related to using ISO 14001 and ISO 9001 standards as a foundation for their SCM procedures. The analysis of the hospitals selected depending on their application of the standards, the type of services provided and the approach to managing medical waste will allow for identifying green SCM practices associated with referring to ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 in different national contexts.

The findings will be helpful for administrators in hospitals to choose the optimal ways to apply ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015 standards in their country. Moreover, it is critical to pay attention to the focus on the comparison of greening supply chains in Australia and Turkey that allows for determining factors that influence the quality and performance of adopted SCM practices. This approach will help managers from different countries to analyze what techniques are most applicable to their specific contexts following the historical changes and the current advanced demands (Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Chakraborty, Bhattacharya & Dobrzykowski 2014; Zainudin et al. 2014). In addition, it is also necessary to consider the fact that the study findings will contribute to improving the healthcare sector of Australia and Turkey while determining the most efficient green SCM procedures with reference to policy evolution in this area.

Statement of Significance

This research has both theoretical and practical significance. The conducted study adds to the existing knowledge and theory on green SCM strategies and practices in different national contexts, especially in the healthcare industry with its specifics. SCM in hospitals and, especially, GSCM are not well covered and discussed in the modern literature on management in hospitals in order to conclude what greening strategies and practices can be discussed as more or less effective in this or that context (Shen 2013; Silvestre 2016; Toke, Gupta & Dandekar 2010). As a result, more research is required in this field. In addition, the study potentially contributes to the generation of new knowledge following the pursuit of the more comprehensive investigation of green SCM strategies per the recommendations of ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 900-2015. Moreover, the study addresses new areas of research, such as the impact of greening and these standards on public and private sector hospitals in Australia and Turkey, along with the challenges connected with implementing such changes.

Furthermore, one of the factors that can maximize the study’s significance is the analysis of the increased impact of the healthcare sector on the natural environment, as well as a rising interest in seeking specific ways to diminish this influence. The reason is that the transition to environmentally friendly management strategies, as well as the focus on the legislation strictly controlling the level of impact on the natural environment, is a common tendency across most developed states (Mbaabu 2016; Min 2014). Still, the existing research in this area related to the contexts of such countries as Australia and Turkey does not cover this topic completely. The Australian and Turkish governments are currently taking their first steps in the direction of applying the principles of GSC in their hospitals, and numerous challenges and complexities are connected with the abovementioned transition due to a lack of appropriate theoretical and practical instruments and recommendations for making the process effective and productive (Böhme et al. 2014; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). Thus, additional research is required and expected in the field.

It is also important to state that the proposed research is of practical significance, and this aspect can be viewed and explained at several levels. Firstly, this study can be helpful and viewed as relevant for healthcare units in Australia and Turkey because they will receive within the framework required for implementing this challenging transition. Moreover, this study will illustrate the best methods of incorporating a theoretical investigation into the practical experience with the focus on green SCM approaches in hospitals of Australia and Turkey. As a result, recommendations provided in the study can consequently be applied by different healthcare organizations and units from similar contexts in order to avoid the most common problems in SCM, as well as maximize benefits. Moreover, the proposed research can be consulted and utilized by different companies across other industries to modify their practices in addition to learning how to adopt GSC.

Overall, it should be taken into consideration that administrators and managers can use the proposed findings to reduce environmental expenditures and the volume of resources utilized to make supply chains more effective. In addition, they will be able to focus on green management according to the principles and criteria associated with ISO 14001-2015 and ISO 9001-2015. From this perspective, the research demonstrates the significant potential value and connection to modern knowledge and practice.

Conclusion

GSCM is an emerging topic of substantial importance for various organizations. However, it is currently mostly being considered in the context of its utility to various manufacturing companies, where it is relatively simple to discern the patterns of pollution generated throughout the supply chain. On the other hand, in healthcare, the topic remains inadequately explored, and managers are often unaware of it or see little reason to adopt it given their work environment. However, in cases where it has been applied, the potential for substantial improvement has been discovered. Moreover, the ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 frameworks appear to be suitable for application in the healthcare industry through different approaches, notably those of Australia and Turkey. As such, a comparison between the two to determine the viability of green SCM and the approach that generates the most success is warranted for the further development of the relevant theory.

Historical Background

This chapter will address the background of the healthcare systems in the domain of their SCM. The concept of SCM has been used in business for over forty years. Whereas, the notion of sustainable SCM practices has existed thirty years ago. The process of SCM is complex in its nature, and the decision to move towards green practices, considering that this concept has been developed recently and that little literature and recommendations exist on this topic, is a challenge for contemporary healthcare organizations.

To structure this study and the interpretation of the results, the authors have used a research framework. This research has used a Technology Organization Environment framework, which is an approach that allows reviewing a technology-linked phenomenon from an organizational perspective (Chiu et al., 2017). Under TOE, there are three primary factors that determine whether an organization will accept a technology-based change or not, which are: usefulness, internal issues, and business environment (Chiu et al., 2017). This means that for the successful adoption of GSCM frameworks, the organizations have to have a suitable company culture and no internal managerial issues, as well as an established service provision strategy. Additionally, the change in question has to provide an evident benefit for the business, which in part means that the effect on the company’s bottom line has to be positive. Finally, the competitors, business partners, and suppliers have to be prepared to support the change. In the healthcare environment, TOE means that the hospital’s management has to be prepared to implement the changes that are needed to support GSCM and sustainability, for example, address waste management issues or energy consumption problems. Additionally, the suppliers that cooperate with these hospitals have to have the capability to produce the items and materials that align with the sustainability requirements. The TOE framework allows one to look at the GSM from a structured perspective, analyzing the varied factors that impact the success of implementing GSCM.

The more recent studies on GSCM and the implementation of green practices in hospital management produce mixed results. For example, Fahimnia et al. (2018) conclude that hospitals under their investigation experienced negative trade-offs when implementing GSCM since this approach was more costly when compared to the traditional or robust SCM. The authors note that there are industries where GSCM is especially effective, for example, for fresh food companies, GSCM means that the product is delivered in limited quantities and within specific time frames, which helps limit the amount of waste, preserve the environment, and save costs for the businesses. For hospitals, however, there is a need to invest in GSCM and sustainable practices, which does not produce results as effective as for other industries.

The question of balance between sustainable SCM practices, costs, and retention of the SC’s robustness remains an important topic in the literature. Fasan et al. (2021) argue that the main benefit of the traditional supply chains is their robustness, which is the ability of the SC to withstand a disaster, which is not the case with sustainable SC. Haiyun et al. (2021) analyze the efficiency of GSCM strategies using the QFD (quality function deployment) framework and conclude that understanding the customer’s expectations and having a proper customer relationship management system in place is the most important element for managing GSCs. By assessing the expectations of the consumers, the organizations can find a better balance between sustainable practices and the profits they want to retain from their operations. For hospitals, this might mean assessing the needs and expectations of the community members and policymakers to balance the profits with sustainability. Moreover, Haiyun et al. (2021) found that having a research and development department is helpful for organizations that aim to implement green practices since innovation is linked with sustainability, and these departments can help transform the operations of the business in general. Finally, Hayun et al. (2021) report that having an assessment of stakeholders’ opinions from different parties is an effective way to determine the strategies that the management should implement for sustainability. Thus, some studies link sustainability and implementation of GSC and the effectiveness of these strategies with the expectations of the stakeholders.

As was mentioned in the introduction, the notion of GSC management has existed for over thirty years; however, this approach has not gained sufficient attention from researchers and practitioners until recently. Agi et al. (2020) report that only within the past three years has there been an increase in the number of publications regarding GSCM, while before, the number of published articles was limited. However, the authors also note the majority of these papers are statistical models and two-level SCM structures (Agi et al., 2020). This suggests that little attention is given to the practice of implementing SCM strategies, which means that managers have limited access to the information and case study materials that would show them the best practices of GSCM. Agi et al. (2021) suggest that researchers focus on developing stochastic models and complex level GSCM to aid the practical implementation of this approach. Hence, this research paper contributes to the body of knowledge on GSCM in healthcare and addresses a critical gap in the literature, which is the lack of case studies and empirical data that would explore the experience of hospitals that have implemented GSCM strategies.

GSCM can be divided into internal supply chain management practices and external strategies. Stekelorum et al. (2021) argue that contemporary organizations have to embrace both strategies as the stakeholders require changes both in the way a company or institution operates and in how they procure the resources required for operations. Green supply is an external practice that many profit-oriented organizations have already adopted, which prompted the suppliers to change their operations and resort to environmentally friendly practices (Stekelorum et al., 2021). This suggests that currently, it is easier for companies to implement green practices as the infrastructure has evolved to support this approach and many suppliers understand the demand and the need to use sustainable production approaches. However, similarly to other studies explored in this review, Stekelorum et al. (2021) point to the mixed results of the financial performance that these firms show, as in many cases, GSCM leads to a decrease of costs, but only in specific industries. The main issue with GSCM is the high cost of the initial implementation, meaning that firms have to invest substantial financial resources into the initial implementation of GSCM. In many cases, the investment is justified as this practice reduces inventory investment and asset recovery, but the timeframe required for these benefits is also longer when compared to traditional SC. Again, this study points to a need to investigate GSCM further to develop a best practice approach suitable for organizations in terms of business benefits and stakeholders’ expectations.

Another important aspect of GSM is its potential positive impact during crisis or disaster times. An important feature of the traditional SCs is their robustness or their ability to withstand a natural or human-made disaster while retaining the same outputs, which is linked to the well-developed network of these types of supply chains. Fasan et al. (2021) report that US companies that used GSCM networks were able to withstand the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic better when compared to those using the traditional SCs. This suggests that GSCM has the potential of being more crisis resilient, which is especially important for the healthcare industry.

Thus, the literature has been critically analyzed to explore the gaps that exist in understanding the GSCM practices and their application in services. The TOE framework provides three critical elements that determine the success of implementing a technology-based innovation into the operations. However, TOE has not been used to explore the specifics of sustainability and GSCM in particular. Moreover, little research exists that addresses TOE and the application of GSCM in the healthcare industry, while the stakeholders, such as policymakers, consumers, and international organizations, pressure healthcare institutions to use sustainable practices.

History of Supply Chain Management in Healthcare in Australia and Turkey

In 1982, the concept of SCM was used to only explain to organizations the specifics of logistic management concerning different types of organizations and providers of resources and services (Asgari et al. 2016). Later, SCM was “integrated with the sustainable development concept to create many new trends in the academic field,” and the idea of “sustainable SCM was proposed by Linton in 2007” (Liu et al. 2017, p. 422). While the realization of SCM principles in the healthcare industry is a challenging task, managers are focused on reaching the goal of developing effective hospital supply chains.

These processes are associated with mitigating increases in expenses, improving resource usage, and patient care quality improvement. Nevertheless, the process of moving to the efficient SCM is complex, and currently, only a few healthcare industries worldwide can be characterized by having strategically efficient and collaborative supply chains including hospitals (Maleki & Cruz-Machado 2013; Rakovska and Stratieva 2018). The problem is that supply chains involving hospitals can be viewed as fragmented because of participants’ independent activities in these chains (Gerwig 2015; Polater, Bektas and Demirdogen 2014). In the healthcare sphere of Australia and Turkey, SCM is related to developing efficient structures and systems of governing hospitals and other facilities, developing productive relationships with suppliers, improving procurement and resource management, and implementing IT systems (Agarwal et al. 2016; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016).

Supply chains are based on a series of interdependent transactions between all participants of the chain, and much attention should be paid to their collaboration. The major participants of healthcare supply chains in Australia and Turkey include different types of manufacturers, such as providers of equipment, specific hospital supply, and pharmaceutical companies, distributors, individual providers of specialized medical services, insurance companies, transport operators, national and state agencies, governmental authorities, employers, and patients (Agarwal et al. 2016; Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Böhme et al. 2014; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). The success of the work in a hospital depends on the cooperation of all these actors because they need to guarantee the on-time delivery of high-quality services for the population. Currently, the authorities in both Australian and Turkish hospitals are oriented to implementing more efficient SCM practices to make hospitals effectively operating systems. However, they have to contend with the novelty of SCM’s application in the healthcare industry, and many modern hospitals have no experience in integrating the required changes effectively and achieve the goal of optimizing supply chains along with thew associated improvements.

The key SCM-related tasks faced by healthcare administrators in hospitals of Australia and Turkey include improving the management of inventory, facilitating public-private collaboration, and predicting the patient mix to guarantee the efficient use of available resources (Agarwal et al. 2016; Özkan, Akyürek & Toygar 2016). At this stage, administrators and managers of hospitals in Australia and Turkey consider opportunities for developing supply chains in the most efficient manner, and the universal response to this issue is the implementation of green SCM principles (Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016; Chege 2012). Green supply chains address the idea of sustainability not only in terms of the effective utilization of resources and inventory management but also in terms of minimizing waste and an overall negative impact of hospitals’ operations on the environment.

As was mentioned before, SCM application in hospitals is a comparably modern trend, and scholarly literature and practice within the last twenty years have been divided on the topic of GSC. Thus, the focus in hospitals and other healthcare facilities in Australia and Turkey seems to be moved from guaranteeing the high-quality care while using minimum resources to providing high-quality care while minimizing the complexity of all processes and their negative effects on the environment (Agarwal et al. 2016; Bhakoo, Singh & Sohal 2012; Camgöz-Akdağ et al. 2016). When choosing the path of modernizing SCM and even selecting strategies connected with GSC, hospitals all over the globe begin to save their human and material resources, address a community’s needs more efficiently, protect the environment, and reduce expenses (Agarwal et al. 2016; Maleki& Cruz-Machado 2013). Therefore, one of the major strategic goals usually considered by administrators or managers in hospitals is the realization of effective SCM.

One more characteristic of a hospital supply chain in Australia is its dependence on the aspects of total quality management. There are many international, national, and regional standards and guidelines that determine the quality of provided services in hospitals, thus affecting the work of a supply chain (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2015). Furthermore, the variety of these standards is high because specific norms and rules are followed in different regions of Australia, and the healthcare industry of the country is not interconnected, and cooperation within supply chains in different regions is based on various guidelines.