Introduction

Children are not naturally inclined to wash their hands, especially when they play. This is a critical concern since handwashing is an essential element in healthcare and the safety of the kids. However, hand-cleanliness is not age-subjective as adults too need to have clean hands all the time. There is no particular marketing strategy to encourage effective handwashing behavior. One of the main global issues, which has made handwashing critical is the COVID-19 pandemic (Alzyood et al., 2020). Therefore, a good advertisement approach can lead to increased handwashing practices and increase public safety standards.

Poor handwashing practices among young children make them prone to infections acquisition, occurring when they contact contaminated surfaces and then touch their face and mouth. This is one of the main areas that the COVID-19 guidelines show is critical to spreading the virus. According to Jess and Dozier (2020), recommended handwashing practices among children can help reduce various infections, particularly respiratory infection by at least 20%. Recent studies such as the one conducted by Watson et al. (2019) indicate that promotions work better than fear-instilling information, hence the need for strategic marketing concerning handwashing. Understanding this concept can help increase the penetrability of the Soaplay in the target market. For this reason, the current study reviews various theories of motivation and market-entry strategies to make the product sell widely.

This chapter on literature review has been divided into six major areas. The first section focuses on defining the gamification theory in general and its applicability to solving problems. Before mentioning the theory, it is critical to present gamification methodology.

The concept of motivation is described in the second section. The third section describes the logic, which describe why gamification is a useful motivational tool to encourage the children to engage in proper handwashing with soap, thus reducing acute respiratory illnesses and keep COVID-19 away. The fourth section addresses the need for social marketing as a critical intervention for improving handwashing practice, especially among children. The fifth section address how motivation plays a critical in handwashing activities. Several questions are answered regarding behavior change regarding hand-cleanliness. The last part addresses the need for understanding the market audience, which is key in the marketing of the product.

Gamification

The advent of technology brought into light many things or made a lot of things that seemed impossible to be possible. The technological advancements brought new concepts that today have been explored to help ease human beings’ lives and make life on earth bearable. Gamification is one of these concepts that came into being through the video gaming industry, but over the years since its inception, it has expanded beyond technology and became a multi-disciplinary term. The gamification theory has been employed in attempting to push people towards different undertakings (Larson, 2020). To humans, playing games is a natural activity that dates back many years ago. The video game industry is a well-known sector, which has specific features such as keeping an individual interested all the time and getting involved in activities that would otherwise seem less attractive.

Games usually have the ability to grab the attention of an individual in such a way that other distractions are pushed aside. Loss of self-consciousness coupled with time distortion may be experienced by an individual when playing. The experience that gaming brings to an individual’s life is satisfying, thus sometimes it makes one do it at a more significant cost for fun since it has no benefits to moving our lives forward from a social, medical, and economic perspective. This aspect of gaming enlightened many in the industry. It was predicted that it would get even more captivating in the future due to the continued advancement in technology, which cannot be moderated. The impact gaming had on people was taken to a new level, and other industries adopted this concept.

The gaming impact on people was so immense that it was speculated that by 2020, 85% of human’s daily activities would have some game elements. Gamification has been introduced in almost every sector, such as in education and health. Health, charity, training, ecology simulations, e-commerce, child-raising, military training, human resources, and sports activity are some of the many disciplined that have incorporated the concept of gamification. The areas of applicability differ very much depending on the subject. In the military, gamification has been actively used in controlling drones that have revolutionized the war on terror. In the education sector, it has been presented through a segregated learning system, which is divided into levels, thus enabling students to complete various tasks according to the skills earned in a previous lesson. Various awards and leader-boards are always introduced to encourage the learners to engage in different learning activities.

In the healthcare sector, gamification has been instrumental in helping patients with rehabilitation. In the business sector, the concept is already deeply enshrined in their activities because they understand why it is essential to have fun while working. Several companies are increasingly investigating the benefits the concept holds while others are massively adopting through various means such as engineering, marketing, sales, customer relationship management, support, and human resources.

Gamification Methodology and Design

The concept’s methodology defines the core game elements that constitute the gamification system and, as such, they are necessary for designing and building it.

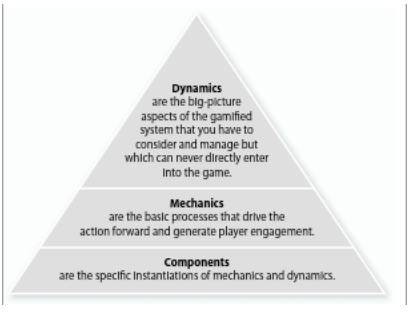

The concept of gamification has three elements: mechanics, dynamics, and components. The linking of these elements is usually done in a particular order to realize effective results.

Dynamics

There are paramont types of gamified system that, alothough they do not constitute part of the game, their consideration is usually vital. This element can be contracted with teaching a kid whereby, to create the needed changes, it is essential that one teaches the kid towards a given direction using applicable practices. Constraints, narrative, relationships, emotions, and progressions form a vital aspect of this element.

Mechanics

This is the concept’s element that seeks to drive action, thus making an individual stay engaged in the process. The exploitation of this element results in the achievement of the dynamics element. The element influences the gamification system’s emotions, thus making them increasingly involved in the task. Social challenges pertaining to social interactions and relationships are also involved in this element. Chance, cooperation, challenge, competition, reward, turn, feedback, win state, and resource acquisition are key in-game mechanics.

Components

There are low-level game elements that are tied to higher-level elements. The element is anchored on the rewards or consequences of an action that, in turn, addresses an individual’s emotions or progression. Achievement, badge, combat, point, quest, level, virtual good, collection, boss fight, leaderboard, team, social graph, gifting, and avatar are key words associated with the element. According to Kowalski and Froiland (2020), rewards play a critical role in motivating kids to do what the seniors desire. As with classroom management and reward system for top performers, other areas, such as constant handwashing should be rewarded, to ensure the children develop a behavior of always keeping their hands clean (Kowalski & Froiland, 2020). Therefore, such awards motivate children in certain ways; thus, they can be used to change their attitudes towards certain directions.

Gamification Design

Gamification systems need careful design to make them effective and efficient. The figure 1 below depicts how game elements need to be coordinated with each other to provide an effective outcome as far as designing is concerned.

The figure above shows that putting the game elements together is a critical task; it is also mentioned that almost impossible to understand and internalize them perfectly (see figure 1 above). Besides, having a list of these elements is insufficient to build something useful and engaging. When designing the gamification system, the list of elements must be chosen based on the situation at hand. For instance, when creating a gamification system that encourages children to wash their hands using soap thoroughly, the list of elements to be used should mirror kids’ behavior and character.

Children Motivation

Motivation is defined as the cause of an individual’s conduct in a particular situation or role influenced by various factors. Several theories of motivation have been developed to address the intrinsic and extrinsic nature of human beings as far as motivation is concerned (Locke & Schattke, 2019). These theories are many, thus it could be overwhelming to discuss all of them; neither will it suit the paper’s purpose. The theories discussed are those that support the topic. The chosen theories belong to the need group, which suggests that one may be willing to participate in productive activies when particular needs are met. These theories are Self-determination theory and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

This theory builds on the idea that individuals are always motivated by the five above-mentioned need levels. The first level of needs encompasses the basic need, and as long as the lower levels are not ensured, the higher ones will have no value (Jiang et al., 2020). The advancement to the next level by an individual is only ensured if the lower-level needs are partially satisfied. The full satisfaction of the needs will not influence a person’s behavior; they will be driven by an intrinsic desire to address higher-level needs.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

The SDT theory is the commonly used theory in gamification. This is anchored on the fact that SDT focuses on experiences of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are essential to the concept of gamification. The theory suggests that three basic needs must always be, as doing this would increase their motivation and productivity (Karimi & Nickpayam, 2017). Thus, if an individual wants to motivate kids to wash their hands thoroughly, then satisfying that aspect that engages them fully will be a significant step towards achieving the goal.

Gamification and Motivation

Gamification has today become a vital part of the motivation theory used by different individuals worldwide. Gamification has its roots in the game industry, while motivation, on the other is commonly based on human behavior (Awadzi, 2018). Needs usually drive an individual to something or make them willing to do something to satisfy the need. Ganification methods can affect some human desires and motives depending on an individual’s personality and the nature of the game. By interacting with various gamification apparatus, one can change their way of doing tasks, thus building a more efficient and better and motivation system.

The concept of gamification seeks to initiate an individual through which the one will be motivated and willing to do anything. Using Soaplay, children will always feel motivated to wash their hands. To the children, Soaplay resembles a ball, and to them, the ball implies playing, and they will always want to do anything to play with the soap (Awadzi, 2018). Thus, is effective to tell kids that the best way to play with the product is when washing hands. This way, kids will always be motivated to wash their hands, and, in the end, this will contribute to the changed behavior of handwashing in children.

Social Marketing Interventions

Social marketing strategies remain a crucial aspect of any planning process. It commonly uses commercial marketing to influence voluntary behavior change among the target market (Da Silva & Mazzon, 2016). According to Da Silva and Mazzon (2016), “Social marketing is a marketing application to induce, encourage, and promote social change entirely, rather than to just provide ideas or information, e.g. cognitive change; otherwise, education and promotion would be enough to solve the issue” (p. 2).

In the public health sector, social marketing is time properly spent, and an investment opportunity which eventually helps the professionals to effect positive behavior change within the target population. It is appropriate when the audience’s needs regarding health benefits are high or medium, behavioral change campaigns are required, or the population deserves better health services (Da Silva & Mazzon, 2016; Green et al., 2019; Lefebvre et al., 2020). However social marketing is not intended to promote public awareness about the product service.

Social marketing intervention strategies target to influence behaviors which benefit society. According to Firestone et al. (2017), it uses concepts such as “product design, appropriate pricing, sales and distribution, and communications” (p. 111). Social marketing assists marketers in making health products and services which are attractive and relatively cheap for medical service providers and buyers. They can avail products at business outlets with subsidized products with the sole intention of promoting an intended behavior (Firestone et al., 2017; Green et al., 2019; Lefebvre et al., 2020).

Social marketing can be promoted through mass media or interpersonal communication channels which may serve to increase client awareness and motivation to use products, over a large audience. By accessing a wide market to promote products, the sales volume is bound to increase significantly. Although several studies claim that social marketing causes behavior change, there is no substantive evidence to back it. Therefore, the perceived impacts of social marketing may mediate behavior change per se.

Children are naturally susceptible to various infections such as respiratory diseases. Based on research by Aronson et al. (2019), their susceptibility is due to their tendency to place objects and their hands in their mouths, noses, or faces. Therefore, infected children can become infection careers to other family members, for instance, their parents, which can fuel the spread of the illness. With the outbreak of the COVID-19 respiratory disease, caused by the coronavirus, which is spread through droplets from an infected person when they cough or sneeze, children remain vulnerable to contracting and spreading the virus. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2020), the most common form of transmitting the virus is having dirty or contaminated hands. Therefore, thorough handwashing with soap or using sanitizers can effectively help in reducing the spread of the illness.

Parents or guardians should involve their children in frequent hand washing practices to promote their health and prevent the spread of the virus. Furthermore, several organizations and businesses have formulated programs to aid families in sensitizing children to engage in handwashing and other preventive measures against the virus spread (Jess & Dozier, 2020). With the naivety that children possess, it is difficult for them to religiously adhere to the handwashing practice. That is why public health organizations have resorted to strategic marketing approaches such as social marketing to effectively change the young ones’ behavior towards washing their hands.

Traditional information-based marketing of products focuses on educating the children on the importance of handwashing. According to Jess and Dozier (2020), it involves “providing rationales and instructions, modeling proper handwashing, and providing vocal and visual prompts” (p. 1220). Another study by Zohura et al. (2020) suggests holding awareness training and education for children about hand-hygiene through multimedia sources, and the relationship between germs and health.

Studies by Besh et al. (2016), Vishwanath et al. (2019), and Tidwell et al. (2019) recommend educating children on hygiene through health agents, health development authorities, and mass media. However, a study by Staniford and Schmidtke (2020) states that traditional information-based marketing strategies are ineffective when they are not supplemented with other approaches. The ineffectiveness could be partly because, by nature, children can participate in the sensitization process with their educators but later they regress to not washing their hands.

Public health organizations can employ strategic approaches of social marketing to influence children’s behavior change with regards to handwashing. They can employ motivation and play elements among children to encourage them to persistently wash their hands. A survey by Ofosu-Ampong et al. (2020) illustrates the use of a game-based curriculum to teach children the frequency and rationale of handwashing.

Other studies (Deochand et al., 2019; Jess et al., 2019) covers the use of video modeling tools to educate children on hand-hygiene. Motion-controlled games were used to inspire handwashing behavior among children with intellectual disabilities in research by Kang and Chang (2019). Kang and Chang used Microsoft’s Kinect V2 sensor to gamify handwashing by adopting a non-concurrent multiple baseline design to illustrate the link between game-based methods and handwashing separately.

In the present times of the COVID-19 pandemic, public health organizations are actively engaging game designers to develop mobile games for children in a bid to enhance human awareness about handwashing. Research by Zain et al. (2020) proposes a game model known as GAMEBC which is based on the self-determination theory consisting of elements such as autonomy, competence, relatedness, and engagement (see Figure 2).

A thesis by López Hernández (2020) also credits gamification with the potential of controlling the spread of coronavirus by children. López Hernández claims that “since evaluation is achieved by an automatic system, players might recognize the assessment to be less stressful or uncomfortable.” (p. 10). López Hernández states that games can marvel at “motivated learners, considering the learning process as an unpleasant but vital step to reach desirable outcomes, while allowing them to experiment with enjoyable outcomes while learning” (p. 11). However, developers must implement functionalities which inspire motivation among the game players by embracing cognitive science concepts.

Another way of motivating children to develop the handwashing habit is by making soaps in the shape of playing toys. During an emergency, children are traumatized and they are inclined to rebel at handwashing and other seemingly life-saving behaviors. By making soaps with toys that marvel them can make them adopt the required behavior. In a study by Watson et al. (2019), children who were provided with transparent soaps embedded with toys (see Figure 3), accompanied with brief entertaining sessions of non-health-related lessons, enjoyed washing their hands, keeping them clean throughout.

Another group was given plain soaps in basic hygiene and health-related session. After four weeks, it was observed that children in the first group were up to four times likely to engage in handwashing than their counterparts in the second cohort. Of the findings, Watson et al. (2019) state that, “our results provide evidence that this readily deployable intervention may be effective at increasing child handwashing practices in a humanitarian setting while facilitating rapid implementation in an often-chaotic humanitarian emergency context” (p. 181).

Other studies continue to support the concept of using soaps fixed toys to promote handwashing among children. In a pilot study by Burns et al. (2018), one group of children received a bar of soap known as HOPE SOAP © every two weeks, while the control was provided with a translucent soap of equal size as HOPE SOAP © at the same interval, but with a toy inside. It was observed that the kids were inclined to voluntarily washing their hands. As a result, they had better health, and less likely to fall ill.

It is conclusive that the visibility of the toy affects other factors in specific studies. In the Watson et al. (2019) study, some soaps were specifically made transparent for visibility of the embedded toy. Since children are curious by nature, assuming they do not destroy the soap to access the toy, they are bound to continuously use the soap. Needless to say, making the soaps opaque so that the toys are invisible to the children may not be as motivating as when they are made transparent. In this case, visibility affects the knowledge attainment regarding the need to maintain hand hygiene. Children who use soaps fixed with toys are likely to gain more knowledge when compared to those with standard soaps (Burns et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2019). The health outcomes of children who are not motivated to engage in handwashing due to their soaps with no toys are also worse than those who use toy-embedded soaps because the latter group continually wash their hands hence better hygiene.

Motivation to Handwashing

There are several attributes which can make children adopt the handwashing with soap (HWWS) behavior. When children are educated about the diseases in terms of the latter’s causative agents, effects, or preventive measures, they are more likely to engage in handwashing. For instance, during the COVID-19 period, children can be taught that COVID-19 is transmitted when individuals come in contact with respiratory droplets from an infected person when they cough or sneeze. The children can also be sensitized to the consequences of contracting the virus, which may include death when the illness is not mitigated. Therefore, when they are informed that HWWS and using sanitizers can help in curbing the spread of the disease, children are more likely to participate in HWWS.

Another attribute which is likely to make children engage in HWWS is the concept of risk. When children believe that HWWS is effective in minimizing outbreaks and spread of illnesses they become motivated to engage the habit (Seimetz et al., 2016; To et al., 2016; White et al., 2020). The belief should stem from the knowledge acquired through learning about the disease. Furthermore, when the children are made aware that there are no preventive or curative treatments for an illness, they will take precaution through self-caring practices.

In the context of COVID-19, before the invention of vaccines (WHO, n.d.), HWWS and sanitizer, coupled with social distancing in public spaces were the surest ways of controlling the spread of the virus. Having this information can inspire children, under the supervision of their parents to religiously wash their hands and use sanitizers. Teaching children that they are vulnerable to contracting COVID-19 by touching their faces, they become conscious of the need to be frequently washing their hands to stay safe from the disease.

Having the HWWS requirements at their disposal can also drive children to develop the habit of hand-hygiene. The availability of a handwashing facility with soap and water sources is a basic requirement to have children wash their hands frequently (Semetz et al., 2016; To et al., 2016). Similarly, having the handwashing facilities and the detergents at convenient locations can inspire handwashing. In the case of controlling COVID-19, having handwashing amenities at convenient entry points of the house, businesses, classrooms, or any other social place where children can access them can motivate them to use the items.

When the handwashing facilities are desirable and user-friendly in design, they are likely to be used by children (Semetz et al., 2016; To et al., 2016; White et al., 2020). For instance, the items can have soap holders, attractive colors, and not too high to be accessed by the kids. The soaps can be scented and embedded with toys to attract children into frequently using them.

Market Audience

Although the main target for HWWS marketing is the children as the consumers, it is appropriate for campaigns to consider their parents who are the customers. The parents are the principal caregivers to their children and, therefore, have the primary responsibility to ensure the safety and good health of their children. Since parents live with their children, marketers must regard and target them with information which they can then relay to their children because they can easily retain and manipulate knowledge.

Parents are usually protective of their children and, hence, can be concerned about what their young ones consume. The marketers should implement ways to convince them to buy handwashing items for their children. Furthermore, only the parents have the monetary ability to purchase items for their children, and at all times they will wish to get value for their money, which is why campaigns should consider the parents too.

Since the children are the final consumers of handwashing products, the focus should be on them during marketing. The marketers should be strategic in their advertising to ensure that the children find their products marvelous and useful. From the explanation, it is the children who influence the parents to buy soap while parents influence them to use the soap. Therefore, parents have the most influence over their children. Out of concern, parents can buy soap then instruct the children to use it.

References

Alzyood, M., Jackson, D., Aveyard, H., & Brooke, J. (2020). COVID‐19 reinforces the importance of handwashing. Wiley Online Library, 29(15/16), 2760-2761. Web.

Aronson, S. S., Donoghue, E., & Shope, T. R. (2019). Managing infectious diseases in child care and schools: A quick reference guide. American Academy of Pediatrics. Web.

Awadzi, C. (2018). Gamification and the future workplace. Human Resource Management, 5(1), 104-108. Web.

Burns, J., Maughan-Brown, B., & Mouzinho, Â. (2018). Washing with hope: Evidence of improved handwashing among children in South Africa from a pilot study of a novel soap technology. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-13. Web.

Da Silva, E. C., & Mazzon, J. A. (2016). Developing social marketing plan for health promotion. International Journal of Public Administration, 39(8), 577-586. Web.

Deochand, N., Hughes, H. C., & Fuqua, R. W. (2019). Evaluating visual feedback on the handwashing behavior of students with emotional and developmental disabilities. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 19(3), 232–240. Web.

Firestone, R., Rowe, C. J., Modi, S. N., & Sievers, D. (2017). The effectiveness of social marketing in global health: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 32(1), 110-124. Web.

Green, K. M., Crawford, B. A., Williamson, K. A., & DeWan, A. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of social marketing campaigns to improve global conservation outcomes. Social Marketing Quarterly, 25(1), 69-87. Web.

Jess, R. L., & Dozier, C. L. (2020). Increasing handwashing in young children: A brief review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(3), 1219–1224. Web.

Jess, R. L., Dozier, C. L., & Foley, E. A. (2019). Effects of a handwashing intervention package on handwashing in preschool children. Behavioral Interventions, 34(4), 475–486. Web.

Jiang, W., Jiang, J., Du, X., Gu, D., Sun, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Striving and happiness: Between-and within-person-level associations among grit, needs satisfaction and subjective well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 543-555. Web.

Kang, Y. S., & Chang, Y. J. (2019). Using a motion‐controlled game to teach four elementary school children with intellectual disabilities to improve hand hygiene. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(4), 942-951. Web.

Karimi, K. & Nickpayam, J. (2017). Gamification from the viewpoint of motivational theory. Italian Journal of Science & Engineering, 1(1), 34-42. Web.

Kowalski, M. J., & Froiland, J. M. (2020). Parent perceptions of elementary classroom management systems and their children’s motivational and emotional responses. Social Psychology of Education, 23(2), 433-448. Web.

Larson, K. (2020). Serious games and gamification in the corporate training environment: A literature review. TechTrends, 64(2), 319-328. Web.

Lefebvre, R.C., Chandler, R.K., Helme, D.W., Kerner, R., Mann, S., Stein, M.D., Reynolds, J., Slater, M.D., Anakaraonye, A.R., Beard, D., & Burrus, O. (2020). Health communication campaigns to drive demand for evidence-based practices and reduce stigma in the HEALing communities study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108338. Web.

Locke, E. A., & Schattke, K. (2019). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Time for expansion and clarification. Motivation Science, 5(4), 277. Web.

López Hernández, M. (2020). Healthcare gamification – serious game about covid-19; stay at home [Master’s Thesis, Malmö University]. Malmö University Publications. Web.

Ofosu-Ampong, K., Boateng, R., Anning-Dorson, T., & Kolog, E. A. (2020). Are we ready for Gamification? An exploratory analysis in a developing country. Education and Information Technologies, 25(3), 1723-1742. Web.

Seimetz, E., Boyayo, A. M., & Mosler, H. J. (2016). The influence of contextual and psychosocial factors on handwashing. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94(6), 1407-1417. Web.

Staniford, L. J., & Schmidtke, K. A. (2020). A systematic review of hand-hygiene and environmental disinfection interventions in settings with children. BMC Public Health, 20(195), 1–11. Web.

Tidwell, J.B., Gopalakrishnan, A., Lovelady, S., Sheth, E., Unni, A., Wright, R., Ghosh, S., & Sidibe, M. (2019). Effect of two complementary mass-scale media interventions on handwashing with soap among mothers. Journal of Health Communication, 24(2), 203-215. Web.

To, K. G., Lee, J. K., Nam, Y. S., Trinh, O. T. H., & Do, D. V. (2016). Hand washing behavior and associated factors in Vietnam based on the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2010–2011. Global HealthA, 9(1), 29207. Web.

Vishwanath, R., Selvabai, A. P., & Shanmugam, P. (2019). Detection of bacterial pathogens in the hands of rural school children across different age groups and emphasizing the importance of hand wash. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 60(2), E103. Web.

Watson, J., Dreibelbis, R., Aunger, R., Deola, C., King, K., Long, S., Chase, R. P., & Cumming, O. (2019). Child’s play: Harnessing play and curiosity motives to improve child handwashing in a humanitarian setting. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 222(2), 177–182. Web.

Werbach, Kevin & Hunter, Dan (2012). For the win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business. Wharton Digital Pres.

White, S., Thorseth, A. H., Dreibelbis, R., & Curtis, V. (2020). The determinants of handwashing behaviour in domestic settings: An integrative systematic review. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 227, 1-13. Web.

World Health Organization (2020). Questions and answers on coronaviruses (COVID-19). Web.

World Health Organization (n.d.). COVID-19 vaccines. Web.

Zain, N. H. M., Othman, Z., Noh, N. M., Teo, N. H. I., Zulkipli, N. H. B. N., & Yasin, A. M. (2020). GAMEBC Model: Gamification in health awareness campaigns to drive behaviour change in defeating covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering, 9(1.4). 229-236. Web.

Zohura, F., Bhuyian, M. S. I., Saxton, R. E., Parvin, T., Monira, S., Biswas, S. K., Masud, J., Nuzhat, S., Papri, N., Hasan, M. T. and Thomas, E. D. (2020). Effect of a water, sanitation and hygiene program on handwashing with soap among household members of diarrhoea patients in healthcare facilities in Bangladesh: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial of the CHoBI7 mobile health program. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 25(8), 1008-1015.