Outline

This paper critically analysis a member of the teaching staff that I have been attracted to on the basis of the qualities displayed by her. An actual incident in the care of patients is described to assist in the critical analysis and the reflection on the qualities of the individual and the actions of the individual. The model of reflection used to guide the reflection is the Gibbs Reflective Cycle.

Introduction

The member of staff that I have chosen for this critical analysis exercise is my mentor. She demonstrates good knowledge of the subject of nursing and providing care to patients. She is also highly skilled in the functions that are required in the provision of care to patients. This has led her to have a strong belief in herself and her abilities. She willingly disseminates her knowledge and skills to her colleagues and skills. In all these aspects she is and continues to remain a role model for me. Yet, there are some aspects of her qualities that have left me in doubt as to whether she should be a total role model for me. It is her belief that she knows what is best for the patient and seldom takes the pain to explain the care activities to the patients and ascertain their views on it. Furthermore, when such views of the patients are available, she tends to ignore them, if they do not agree with her perception of the care needs of the patient.

Theoretical Frameworks

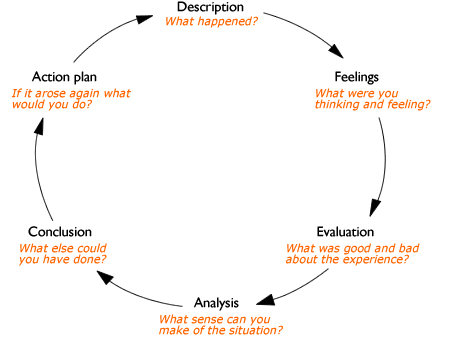

I have chosen the Gibbs reflective cycle as the theoretical framework for the reflection and critical analysis of this incident. A key consideration that has led to the choice is that it is simple and easy to use in the development of one’s self (Jones, 2007). This theoretical framework is the result of the developmental works done by Graham Gibbs in 1998, based on Kolb’s works in educational theory and hence is named after him. It has become a popular reflective model since its inception (Jasper, 2003). There are six elements in Gibbs reflective cycle as given below in figure 1.

Gibb’s reflective cycle is not a static process, but rather a dynamic one that runs through a series of questions that form the structure of the model. It starts with describing what happened and moves on to the emotions and thoughts at the time of the incident. The next step is the evaluation of what was good and bad about the experience and moves on to the learning experience of the incident. The next step in the cyclic process is considering what more could have been done and the final step is developing an action plan should a similar incident occur again, which then sparks off another reflective cycle (Bulman, 2004).

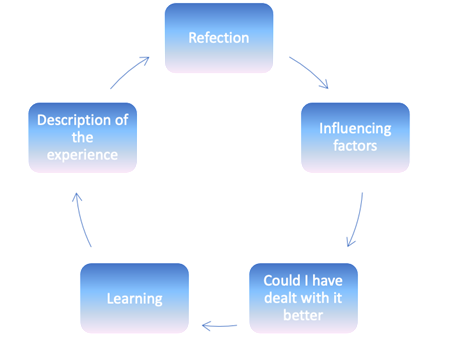

Another theoretical framework that can be used satisfactorily for reflection is John’s model of structured reflection, developed by Chris John in 1993, which stems from the rationale that reflection offers the means of exploring the skills used in the provision and the effectiveness of its use (Royal College of Nursing, 2009). There are five cue questions in this model of structured reflection that enable one to break down an experience and reflect on the process and the outcomes involved. The five steps of John’s structured model of reflection are shown in figure 2.

Essentially there isn’t much of a difference in what is required to be done in the steps of the Gibbs reflective cycle and John’s model of structured reflection, which help in evaluating and understanding what has happened and the outcomes (the University of the West of England, 2007). I have however decided that I will use the Gibbs reflective cycle for the reflection of the incident based on its popularity (Jasper, 2003), simplicity and ease of use (Jones, 2007) and dynamic nature (Bulman, 2004). In addition, Slater 2003 recommends the use of Gibbs’s reflective cycle in reflection exercises on care episodes, because it enables a comprehensive assessment of the episode.

Description of the Incident

The incident that I would like to describe runs as follows. I was on duty on January 20, 2009, along with my mentor. A pregnant woman Mrs. B was admitted into our care. She was 27 years old primigravida woman, with gestation estimated at 39+6/40 weeks. She was booked at eleven weeks as a low risk since there were no medical problems that posed a risk to her pregnancy and delivery. Her religion was given as Christian and married. She was born in Mauritius and had moved to the United Kingdom eighteen years ago. Her husband was to be present during labour, when care was taken over.

I was asked to work out the birth plan details with Mrs. B. During the discussions with Mrs. B on the birth plan, I asked her whether she wanted her baby to be delivered to her abdomen. This was a part of the consent procedure, which allowed Mrs. B to make an informed choice on where the baby was to be delivered. She answered in the negative and instead confirmed her choice of wanting the newborn infant to be cleaned and then handed over to her.

This exercise of taking Mrs. B’s informed consent was to adhere to the guidelines of the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2008 that nursing and midwife professionals have to make sure that informed consent is received prior to any treatment or care (Nursing & Midwifery Council. 2008). McHaffie 1998, citing Dimond 1996 on informed consent states that informed consent constitutes satisfying the following four elements of voluntarily, information, competence and decision.

he time for delivery arrived and I was conducting the delivery under the supervision of my mentor. I had informed my mentor that Mrs. B informed choice was that she did not want the baby delivered on her abdomen, but wanted the baby to be cleaned prior to handing it over to her. This was in keeping with the requirement of the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2008 guidelines that in shared care activities of others all the colleagues involved in the core activities must be kept informed of the informed choice of the care receiver.

Therefore, I was surprised when my mentor gave me instructions to deliver the baby on the abdomen of Mrs. B. I quietly reminded my mentor that this was not the informed choice of Mrs. B. She responded that since the baby was coming from Mrs. B she ought not to have any issues with delivering the baby on the abdomen and instructed me again to deliver the baby on the abdomen of Mrs. B. In this situation, where I was working under the supervision of my mentor, I felt I had no choice but to obey the instructions of my mentor and deliver the baby onto the abdomen of Mrs. B.

I have chosen this incident from the many experiences that I have had with my mentor, as in spite of all that I have learnt from her knowledge and expertise in the care of patients and she remains my role model in these aspects, this is one instance that has confused me and I believe is worth recollection, analysis and reflection.

Feelings

To my mentor, there was nothing wrong with what had happened. She strongly believed the right place to deliver a baby was on the stomach, irrespective of whatever be the considerations of the mother on where the baby was born. To my mentor, the newborn infant was an extension of the mother in the final stages of its attachment and the mother need not have aversion to the delivery of the baby on the abdomen.

Her better knowledge of what was best for the mother and baby gave her the right to overrule any choice that the mother may have made that ran against this grain of thought. Such an attitude tallies with the finding of Aveyard 2004, who studied the manner in which nursing care was provided to patients in the United Kingdom. The study suggests that nursing professionals do go through a lot of effort in getting voluntary consent for the care to be provided, but in case the informed choice does not concur with the preferred care provision of the nursing profession, the care provided quite often ignores the informed choice of the patient (Aveyard, 2004)

The patient fazed by the pains of labour was unaware and unconcerned of where the baby was really delivered. She only wanted the pains of labour to end and was glad when it was over. The husband attending on the delivery was unaware of the informed choice of Mrs. B. That left only me that with the burden of the feeling of wrongdoing and the sense of guilt.

Evaluation

The only thing good about the incident was that the delivery went off smoothly and there were no untoward events for the newborn and mother. My mentor was happy with the smooth delivery and the husband was blissfully unaware of the wrong that had happened, happy that his wife and child were fine. It was only me that had a bad feeling in the mouth at the end of the incident. I knew my mentor and I had done wrong. We had ignored a valid advance directive of not delivering the newborn on the abdomen of the mother and had got away with it because the mother was in no position to be aware of it from the after effects of the labour pains she had endured and the husband was unaware of the advance directive. The advance directive was a valid one and given by Mrs. B. It was binding on my mentor and me in the delivery of the new-born (Samanta & Samanta, 2006).

Analysis

The analysis of the incident has to be done from legal and ethical perspectives in addition from the view of professional standards for nurses and midwives. Informed consent is a process that has significant implications for nursing and midwife professionals from both the legal and ethical perspectives. It is this process that makes a patient a part of the decision process in care provision and is important in that it assures care in the best interests of the patients (Carl, 1997).

The Department of Health in its Good practice in consent implementation guide: consent to examination or treatment clearly indicates that it is “a fundamental legal and ethical right” of a patient “to determine what should happen to their own bodies” (Department of Health, 2001). Consent needs to be sought in all forms of health care provisions and though the delivery of the newborn onto the abdomen may seem trivial, it was still the legal and ethical right of Mrs. B to deny approval for delivery of the new born on her abdomen.

Thus, the action of my delivering then baby on the abdomen of Mrs. B, on the instructions of my mentor, was a breach of the fundamental legal and ethical rights of Mrs. B. The Department of Health Standards for Better Health 2004, make it essential that the delivery of treatment and care to patients is done in accordance “their individual requirements and meet their physical, cultural, spiritual and psychological needs and preferences”, in the interests of maintaining professional standards in the health care sector. Therefore, the action of delivering the baby on the abdomen of Mrs. B was not in keeping with the standards expected of health care professionals in the health care sector of the United Kingdom.

Conclusion

The question then arises of what could have been done in the given situation to improve the standards of care provided to Mrs. B to uphold her legal and fundamental rights. According to Vaartio et al 2006, p.290, “in nursing practice the abstract concept of nursing advocacy finds expression in voicing responsiveness, which integrates an acknowledged professional responsibility for and active involvement in supporting patients’ needs and wishes”. This advice suggests that the incident could have been avoided if I had stood up for the rights of the patient and played my role in patient advocacy.

The role of advocacy is gets effected through the barriers that are present, which essentially constitute the willingness of the health care professional to stand up for the rights of patients to a senior professional in the same discipline or to other health care professionals and the lack of a culture that encourages patient advocacy in a health care institution (Hanks, 2007). Had I been bolder and confronted my mentor that it was not right to deliver the baby on the abdomen of Mrs. B, this incident might have been avoided. Such a role is not easy to play as Vaartio & Leino-Kilpi, 2005 point out that the role of advocacy is complex and may not be easy to practice in all health care environments. In spite of the complexities and difficulties involved in nursing advocacy, I would have done better, if I had remembered that nursing advocacy is a moral obligation to patients (MacDonald, 2007).

Plan of Action

My plan of action for the future involves the development of patient advocacy skills and overcoming my timidity in standing up for the rights of my patient. In the first place, I will develop interpersonal skills to enable me to communicate effectively with my superiors, colleagues and other health care professionals. I will also study theoretical models like the sphere of nursing advocacy model that shows how to encourage patients to self-advocate for their rights and in case they are not in the capacity to do so, enable me to stand up for their rights in an efficient manner (hanks, 2005).

Literary References

Aveyard, H. 2004, ‘The patient who refuses nursing care’, Journal of medical ethics, vol.30, no.4, pp.346-350.

Bulman, C. 2004, ‘Help to Get You Started – Reflecting on Your Experiences’, in Reflective practice in nursing, Third Edition, eds. Chris Bulman & Sue Schutz, Wiley- Blackwell: New Jersey, pp.161-180.

Carl, R. R. 1997, ‘Informed consent: ethical and legal implications for nursing practice, The Oklahoma nurse, vol.42, no.4, pp.18.

Department of Health. 2001, ‘Good practice in consent implementation guide: consent to examination or treatment. Web.

Department of Health. 2004, ‘Standards for Better Health’. Web.

Hanks, R.G. 2005, ‘Sphere of Nursing Advocacy Model, Nursing Forum, vol. 40, no.3, pp.75-78.

Hanks, R. G. 2007, ‘Barriers to nursing advocacy: a concept analysis’, Nursing forum, vol.42, no.4, pp. 171-177.

Jasper, M. 2003, Beginning Reflective Practice. Nelson Thornes: Cheltenham, U.K.

John, C. 2004, Becoming a reflective practitioner, Wiley-Blackwell: New Jersey.

Jones, J. 2007, ‘Do not resuscitate: reflections on an ethical dilemma’, Nursing standard, vol.21, no.6, pp.35-39.

MacDonald, H. 2007, ‘Relational ethics and advocacy in nursing: literature review’, Journal of advanced nursing, vol.57, no.2, pp.119-126.

McHaffie, H. 1998, ‘Gaining ethical approval: A necessity or an optional extra?’ Midwifery, vol.14, no.2, pp.101-103.

Nursing & Midwifery Council. 2008, ‘The Code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives’. Web.

Quinn, F. M. & Hughes, S. 2000, The principles and practice of nurse education. Fourth Edition, Nelson Thornes: Cheltenham, U.K.

Samanta, A. & Samanta, J. 2006, ‘Advance directives, best interests and clinical judgement: shifting sands at the end of life’, Clinical medicine, vol.6, no.3, pp.274-278.

Slater, W. 2003, ‘Management of faecal incontinence of a patient with spinal cord injury, British journal of nursing, vol.12, no.12, pp.727-734.

University of the West of England. 2007, ‘Brief information on models of reflection’. Web.

Vaartio, H., Leino-Kilpi, H., Salantera, S. & Suominen, T. 2006, ‘Nursing advocacy: how is it defined by patients and nurses, what does it involve and how is it experienced?’ Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, vol.20, no.3, pp.282-292.

Vaartio, H. & Leino-Kilpi, H. 2005, ‘Nursing advocacy-a review of the empirical research 1990—2003’, International journal of nursing studies, vol.42, no.6, pp.705-714.